Weather in Motion: A 50-year lookback at Earth’s first movie debut

On December 7, 1966, the world’s first geosynchronous Applications Technology Satellite (ATS-A) launched from its pad at Cape Canaveral. Two weeks later, the satellite reached its orbit over the equator and the Pacific Ocean. Images from ATS-I—and the movies constructed from them—would revolutionize the way we look at Earth and its weather. Motion pictures of Earth’s weather would soon become the new norm—benefitting atmospheric research and forecasting everywhere.

ATS-I’s historic journey started in the mid-1960s with a proposal to NASA to build the first geosynchronous satellite. Around the same time, the late Verner Suomi (founder of the UW-Madison Space Science and Engineering Center) and UW engineering professor Robert Parent wanted to capitalize on the geosynchronous orbit of ATS to better observe Earth’s weather patterns.

Their proposal led to an innovative design called the Spin-Scan Cloud Camera, which sensed visible or reflected radiation.

“The object of this experiment is to continuously monitor the weather motions over a large fraction of the Earth’s surface,” wrote Suomi, citing the information gaps left by polar orbiting satellites. “Even though near Earth weather satellites have provided an impressive array of visual and infrared observations of the Earth’s weather on a nearly operational basis, the synchronous satellite affords another opportunity to gain a better understanding of the global weather circulation, the key to better weather prediction.”

According to Suomi, the premise was simple: “The weather moves, not the satellite.”

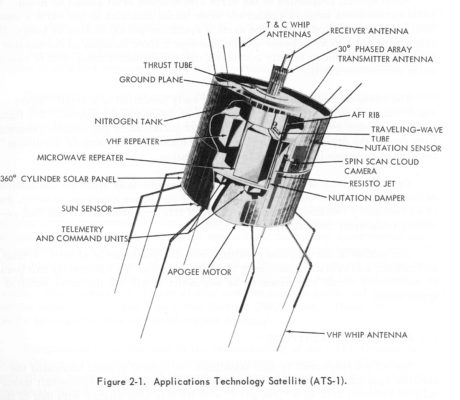

The ATS-I geosynchronous satellite launched December 7, 1966. Credit: Applications Technology Satellite Meteorological Data Catalog: Volume I, NASA

By utilizing the satellite’s rotation while in geosynchronous orbit, ATS-I was able to capture full-disk images of Earth and beam them back every 20 minutes, revealing never before seen detail of cloud motion. ATS-I and its spin-scan camera were fixed over the Pacific Ocean, which Suomi and Parent described as being “the ‘boiler’ of the giant atmospheric heat engine.”

The spin-stabilized spacecraft, shaped like a large drum, measured 4.4 ft. long and 4.6 ft. in diameter. Relative to today’s satellites, ATS-I was compact, but marked the beginning of a long series of geosynchronous satellites to come.

Shortly after receiving the first images, Suomi produced a rough, yet functional, video of Earth and its cloud formations over the Pacific Ocean in January 1967. Suomi took his short film to a conference in Washington D.C. the following week where he received a standing ovation from the audience of scientists and administrators. The video quality would quickly improve with the help of Suomi’s graduate student Fritz Hasler, whose interest in engineering and filmmaking led him to develop an efficient method for compiling all of the ATS-I scans, aligning them into a motion picture. The team would later produce several videos with footage from ATS-I. Hasler described the communities’ initial reception of the first videos to have quickly gone from a sense of curiosity and intrigue, to a rapid high-demand for more of these kinds of videos with improved detail.

An illustration of ATS-I. The satellite doubled as a communications hub and was part of a the world’s first global TV show broadcast, airing The Beatles song, “All You Need is Love” in 1967. Credit: NASA Earth Observation Systems

Prior to the launch of ATS-I, the world had seen only snippets of Earth’s surface, with the first in 1946 coming from cameras strapped to WWII V2 rockets. These cameras were only able to capture images of the clouds and parts of the Earth’s surface. It wouldn’t be until 1966, when NASA’s Lunar Orbiter 1 took the first photo of Earth from the Moon as it surveyed its surface for potential landing spots for the upcoming Apollo 8 mission. The Lunar Orbiter captured these images just months before ATS-I would send back its motion pictures.

Less than a year after ATS’ first launch, ATS-III went into orbit carrying a newly designed camera made by Suomi and Parent, this time located over the Atlantic Ocean and South America, viewing parts of North America and Africa. In November 1967, ATS-III sent back the first color images of Earth, which were similarly compiled into movies.

ATS-I set in motion a series of new geosynchronous satellites to be used for both communications and meteorology. Beyond their immediate scientific uses, the captivating images would become commonplace in nearly every media, from textbooks to posters, to film, screen savers, and postcards. Geosynchronous satellites, first operational in 1975, would continue to send data which would dramatically improve our ability to forecast weather events.

UW-Madison, the birthplace of satellite meteorology, is so-known because of Suomi’s vision to use satellites as a platform for viewing and learning about Earth and its atmosphere. His legacy, and that of ATS-I, can be seen today through the succession of satellites which followed, continuously advancing our understanding of the Earth.

by Eric Verbeten