SPARC-ing student interest in fieldwork

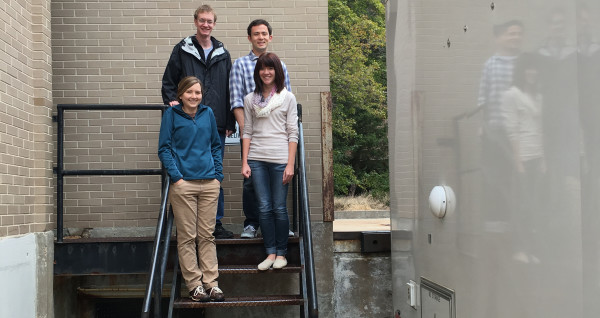

Four UW-Madison students supported SSEC’s participation in the Plains Elevated Convection At Night (PECAN) field campaign. Back: David Loveless and Coda Phillips. Front: Michelle Feltz and Skylar Williams. Credit: Sarah Witman, SSEC.

This summer, more than 100 scientists from across the country gathered in Hays, Kansas, for the Plains Elevated Convection At Night (PECAN) — a major meteorological field experiment supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA), and the Department Of Energy (DOE).

Throughout most of June-July 2015, these scientists collected ground-based weather data using a variety of scientific instrumentation onboard eight mobile radars, six fixed sites, four mobile labs, and three research aircraft. Those data could help provide answers about how convection and storms form after sundown — a common but poorly understood phenomena in Great Plains states during the summertime.

Much of the manpower involved in PECAN — helping with instrumentation setup and takedown, maintenance, data management, and other necessary tasks — were students.

A handful of University of Wisconsin-Madison students who, through their involvement with the Space Science and Engineering Center (SSEC) on campus, spent a week or more conducting fieldwork at PECAN – gaining practical experience and embodying the university’s mission to inspire and train future scientists.

UW-Madison graduate student David Loveless launching a radiosonde into some mammatus clouds in Red Oak, IA. Credit: John Lalande, SSEC.

David Loveless

Graduate Student

Atmospheric Science

Growing up in New Jersey, David Loveless had few opportunities for storm-chasing.

“I would go out and take video of lightning, but that was about it,” he recalled.

In his first year as an atmospheric sciences graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, though, Loveless has been able to spend several hundred hours out in the field — assisting with instrumentation for the PECAN field campaign. He will write his master’s thesis based on several case studies from the campaign.

“I like doing operations-based research that has obvious real-world applications,” he said.

Based in Hays, Kansas, PECAN is the first major collaborative attempt to improve scientists’ cloudy understanding of how nighttime convection and thunderstorms form. The campaign strongly aligns with one of Loveless’ main research goals: conducting science that could directly impact weather forecasting. So, when the opportunity arose to travel to PECAN, it was a natural fit.

Loveless went on the road with UW-Madison’s mobile lab — the SSEC Portable Atmospheric Research Center (SPARC) — a utility vehicle equipped with instruments capable of detecting environmental conditions such as air temperature, particle size and density, and wind speed and direction. The SPARC is managed by SSEC scientists Erik Olson and Lee Cronce, who helped train the SPARC crew at PECAN.

After three (non-consecutive) weeks at PECAN, Loveless learned how to set up and take down instrumentation, and — perhaps more importantly — understand the root causes of errors and inconsistencies in the data.

“I am learning a lot about the instruments I am working with,” he said. “With remote sensing — making measurements from a distance — seeing your instrument, knowing how it works, and knowing what kinds of things could mess up your measurements is important.”

During the first week of PECAN, for example, the air conditioner in the SPARC was not working properly, causing problems with one of the instrument’s sensors.

“We could look at the dashboard on the computers and see that the measurements were off a little bit. I would never have known that if I had not been out in the field,” he said. “It’s obvious if you think about it, but the environment in which your instrument is running really affects your data.”

At PECAN, Loveless worked primarily with two of the SPARC’s instruments: an Atmospheric Emitted Radiance Interferometer (AERI), which measures radiant energy from the Earth’s atmosphere, and a WindPro lidar system that uses reflected light to record wind direction and speed profiles. Since these instruments do not work well in rainy conditions — the drops of rain block their sensors, causing gaps in the data — Loveless will most likely choose relatively dry missions as case studies for his thesis.

Each Intensive Operations Period (IOP) deployment during PECAN was assigned a science objective based on one of four pre-convective formations — a bore, a low-level jet, a mesoscale convective system, or convective initiation — by a mission selection team. The team — made up of scientists such as SSEC’s Tim Wagner, Chris Rozoff and Wayne Feltz, who is a Primary Investigator for the experiment and Loveless’ mentor — used the best available science and models to position the network of mobile units in the path of one of these four formations.

The driest missions, generally, involved weather phenomena called bores – cloud ripples that occur when two air masses of disparate temperatures meet.

“We have been able to get good data with all instruments all the way through on a few bore cases,” Loveless said. “I have always been fascinated by bores; I just like waves for some reason. I also don’t know much about them and this is a good opportunity to learn more.”

He said he will look for instances in which, while moving through space and time, a bore experienced notable changes in structure.

“I want to know, ‘Why is it changing? Why did the bore initiate convection here and not there?’ That would be interesting,” he said.

Using radar from the National Weather Service and PECAN’s mobile units, Loveless hopes to be able to clearly identify a bore’s location from a specific mission, and match it up to SPARC data. Even better, he might be able to track the evolution of a bore passing over both the SPARC and the CLAMPS, a similar mobile unit operated by Dave Turner at Oklahoma University.

In the future, the SPARC and CLAMPS may do more experiments together, to pursue a shared vision of creating a nationwide network of thermodynamic instruments.

Based on his positive experience at PECAN, Loveless said that, if possible, he would welcome the opportunity to go out into the field again. He expressed confidence that, when he sits down to parse through the data later this year, his time spent in the throes of action will provide some added motivation and insight.

“Personally, the most interesting cases are when I was out there. Because I was in it, I know what was happening. I am able to pull that from memory, and already have that naturally driven curiosity from experiencing the weather that day and wanting to go back and look at it,” he said.

Loveless chose UW-Madison for graduate school intending to study satellite remote sensing under atmospheric sciences professor Steve Ackerman, director of the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS) and a fellow alumnus of Loveless’ alma mater, State University of New York at Oneonta. Although satellite meteorology is still close to his heart, Loveless said he has enjoyed this temporary immersion in ground-based remote sensing.

The lessons he has learned out in the field, he said, translate to all areas of science.

“I have learned from PECAN that, out in the field, you need to learn and solve problems as they come up,” he said. “If something breaks, you need to decide whether to go back or go on with what you have.”

UW-Madison graduate student Michelle Feltz gets ready to drive a university vehicle used for transporting additional instrumentation and equipment for the SSEC Portable Atmospheric Research Center (SPARC). Credit: Sarah Witman, SSEC.

Michelle Feltz

Graduate Student

Atmospheric Science

Spending several weeks at PECAN, UW-Madison graduate student Michelle Feltz’s duties included assisting with instrumentation setup and takedown for the SPARC, as well as writing daily blog entries from the field about weather conditions and other notable events during each deployment.

After earning her bachelor’s degree from UW-Madison’s Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, Feltz dove straight into graduate school. She plans to complete her master’s this fall, and then continue with her research.

Fieldwork has been an integral part of Feltz’s education. In 2013, she traveled to northern Wisconsin for the Park Falls campaign, launching radiosondes to validate measurements from GOSAT, a Japanese satellite. That same year, she took part in a calibration and validation program for the Suomi NPP mission, collecting data from the ground in Tucson, Arizona, as the satellite passed overhead, in order to validate its measurements. She also helped design a mini-campaign as part of an undergraduate course, where she looked at temperature variation across a mountainside in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, using data from satellites and meteorological stations.

“I like being outdoors, so field campaigns are a nice change from sitting behind a computer,” she said.

Although she is no stranger to spending weeks at a time in the field, Feltz’s role with PECAN was more extensive than with past campaigns.

“I had never dealt with the SPARC trailer before, or been involved with setting up instruments other than launching radiosondes,” she said. “I like working with the instruments. My adviser, [SSEC scientist] Bob Knuteson, has told me many times that it is important for students and researchers to know where data are coming from, so they understand the costs involved, and the uncertainties.”

Knuteson himself has collaborated on numerous field campaigns with SSEC — particularly with the SPARC’s predecessor, the AERIbago — so he is intimately familiar with the type of work his student is now doing. In its 20-year heyday, the AERIbago deployed on dozens of field experiments, while PECAN is just the second major campaign for the SPARC since it launched last year.

Now that PECAN has concluded, in mid-July, Feltz said she is eager to get back in the field.

“It’s been really fun, and it has been great to get this experience and knowledge,” she said.

UW-Madison undergraduate student Coda Phillips sets up the SPARC’s anemometer, which measures wind speed and direction. Credit: Sarah Witman, SSEC.

Coda Phillips

Undergraduate Student

Computer Science and Engineering

Coda Phillips, a junior undergraduate student at UW-Madison, spent several weeks assisting with instrumentation setup, takedown, and troubleshooting for the SPARC during PECAN.

Phillips, who has been a student hourly at SSEC since his freshman year, said he was drawn to the position as it offered the chance to use his programming abilities for scientific applications. He is now considering working toward a graduate degree in atmospheric science to further his knowledge in this area.

“My job at SSEC has definitely shaped my interest in this field, and opened the possibility of studying it further,” he said. “I can see myself building a career at the intersection of atmospheric science and computing.”

Phillips also spent the three weeks leading up to the campaign, and several weeks after its conclusion, helping install and remove a network of Atmospheric Emitted Radiance Interferometer (AERI) instruments across the Great Plains with SSEC scientists Denny Hackel and Jon Gero, who is the Principal Investigator for the AERI program.

All eight AERIs — six fixed sites and two mobile units, including the SPARC — collected atmospheric data throughout the campaign.

“It was the first time I, or anyone, had installed that many AERIs. It was an unprecedented array,” Phillips said.

“To be participating in something of this scale is really cool,” he added. “It feels good to be progressing science. I think it’s really important that these kind of experiments happen.”

Although working in the field is not something that Phillips expected when he took the job at SSEC, he said he feels it is a helpful complement to his programming work.

“The more I am in the field, the more I learn. It really helps with problem-solving to work with the instruments and have that knowledge. It gives you a more complete picture,” he said.

As his majors — computer science and computer engineering — might suggest, Phillips enjoys spending a majority of his time working on computers. But, he said, fieldwork is “an important and fun change of pace.”

SSEC scientist Andrew Wagner and graduate student Skylar Williams preparing a weather balloon in Scott City, KS. Credit: David Loveless, SSEC.

Skylar Williams

Graduate Student

Atmospheric Science

Before having ever taken a UW-Madison course, soon-to-be graduate student Skylar Williams traveled to a major field campaign (PECAN) and visualized a complete dataset from the experiment when he returned to Madison.

Williams, who will begin a master’s degree in satellite applications this fall, began working with SSEC scientist Tim Wagner in early July. First, though, she received a hands-on introduction — as a member of the PECAN field team, helping with instrumentation setup and takedown for the SPARC in the final days of the experiment.

“It was nice to be thrown out into the field, to meet people,” Williams said. “David [Loveless] taught me the basics the first night and I learned from there.”

Not only was there a lot of new information to take in, but Williams had to adapt to the inverted sleep schedule necessitated by PECAN’s nighttime deployments. Her first “day” of work lasted more than 24 hours, she recalls — the SPARC’s propane tanks were running low, so the team stayed up to wait for the refilling station to open at 8 a.m. the following morning.

“I am someone who needs a good night’s sleep,” she said, “so right away I was like ‘What have I gotten myself into?’”

Having recently completed her undergraduate degree in meteorology at the University of Oklahoma — located in Norman, Oklahoma, the headquarters of the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center — Williams said she thought she knew storms. Being in Hays, however, was a wakeup call.

“Every night we deployed, we got to see lightning in the distance, see the storm structure growing. I have never seen lightning like that in my entire life,” she said, describing how the flickering lightning, setting sun, and eventual stars set up a breathtaking backdrop for the bright-green beam of the SPARC’s High Spectral Resolution Lidar (HSRL).

“Kansas, Iowa, everywhere else we went it was absolutely beautiful. And it goes on forever because it is so flat,” she said. “That’s not the stuff you experience sitting in front of a computer all day.”

Back in Wisconsin, Williams started plotting data from the Halo Windpro lidar system — some of which were the very same data she and the SPARC team had collected in the Great Plains.

The Windpro collects both vertical and horizontal velocity data. When plotting them, Williams overlays the two datasets, so the viewer is seeing barbs of wind at the same time that they are seeing the up-and-down motion of parcels of air, she explained, allowing them to visualize what the wind was doing over time.

The types of plots she created for PECAN are called quick looks, because a scientist can quickly visualize what was happening that day — without having to parse through an array of numbers. If that scientist finds a case of interest, they might go back and make a more detailed plot.

“For example, David [Loveless] is looking at bores, and you can actually see the bores in the wind lidar data. It’s really cool,” she explained. “ They are so much easier to look at this way.”

Making these quick looks has been a helpful introduction to programming, said Williams, bringing her closer to the type of science that drew her to Wisconsin in the first place.

As an undergraduate student, Williams volunteered with the Experimental Warning Program at NOAA’s Hazardous Weather Testbed, an annual event in Oklahoma.

“They have a simulated forecast office, and I helped gather storm reports,” she recalls. “They test a lot of products there that can be helpful for forecasters. I got to see a lot of the products being tested — the ProbSevere model, overshooting cloud tops products, one-minute satellite imagery … I was blown away by how useful these products could be.”

“The more I saw, I knew I had to be involved with this somehow,” she said. “This is what I want to do.”

Now that the academic year has commenced, Williams will likely continue to be involved in SSEC projects with Wagner, who is now her research adviser.

Wagner’s interest in working with students derives from his own positive experience, he said. As a graduate student at UW-Madison, Wayne Feltz and Dave Turner, two of his mentors, arranged for him to spend three weeks in Chile on a field campaign.

“It was an environment that I never would have been exposed to otherwise,” he recalled. “Getting students out in the field takes classroom learning to the real world. To truly understand science, you need to experience it directly.”

Students bring a different perspective and “new eyes” to the table, said Wagner. Plus, some extra youthful energy can be helpful on a nighttime deployment-heavy campaign like PECAN.

“I don’t know how you do a field campaign without students,” he said. “They are the frontline workers that keep these big science projects going.”

This educational component has always been a vital part of the SSEC mission, Wagner explained. Likewise, the Wisconsin Idea purports that the university should extend beyond the classroom – statewide and globally.

“These students are making a real contribution, generating future cutting-edge science,” he said. “This is not busy work. The fact that students can get in on the ground floor serves us while, at the same time, giving them valuable experience they can take with them into their own scientific careers.”

PECAN concluded on July 15, 2015. For a full recap on the experiment, read the rest of our coverage on SSEC News and check out #PECAN15 on social media.