Super Rapid Scan Imaging: Tracking Severe Weather Minute-by-Minute

As severe weather develops, it can change rapidly, necessitating equally rapid updates to watches and warnings issued by forecasters. But imagers on current geostationary weather satellites in the United States routinely generate imagery only every 15 to 30 minutes, not frequent enough when severe storms are developing and changing quickly.

Researchers at the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Center (CIMSS) and the Space Science and Engineering Center (SSEC) in collaboration with scientists from NOAA’s Advanced Satellite Products Branch (ASPB) stationed at the UW-Madison are preparing for a powerful new imager that will be standard equipment on the next generation of weather satellites launched by NOAA in late 2015. Known as Super Rapid Scan Operations for GOES-R (SRSOR), the current imager is used in a special mode to produce snapshots of weather conditions nearly every minute, an unprecedented timescale.

Tim Schmit, an ASPB scientist working in Madison, explains that, “These super rapid scans show you what is happening, not what has happened. The special scans from GOES-14 allow us a glimpse into the improved temporal sampling that will be routinely possible with the next generation imager.”

The SRSOR has been tested a couple of times in the past year – one of which was during Hurricane Sandy, when researchers from CIMSS requested that the imager be turned toward the eastern United States. Operational weather forecasters got an immediate glimpse of the power and capability of the SRSOR as it returned images of the developing hurricane. And more recently, the imager was activated on June 12-13 when the Storm Prediction Center in Oklahoma warned that the Midwest, including Wisconsin, could experience a combination of tornadoes, high winds and hail on those days.

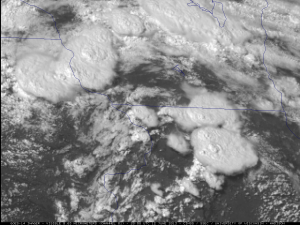

Scott Bachmeier, a CIMSS scientist, processed SRSOR data on June 12-13, detecting “the appearance of “feeder band” clouds that were flowing into the western edge of the large thunderstorm.” Schmit notes that this frequency is not possible with the current operational imagers. The SRSOR will provide a unique perspective on developing atmospheric conditions and phenomena.

- GOES-14 0.63 µm visible channel images. Credit: CIMSS, SSEC, UW-Madison.

The SRSOR will be activated again in August 2013 to track hurricane development. It will collect data in parallel with the Global Hawk, an unmanned aircraft equipped with sensors to monitor hurricane evolution. Scientists will be able to evaluate what each instrument “sees” and compare strengths and weaknesses of current versus next generation observations.

While the SRSOR is still in its testing phase, it is anticipated that the imager’s data, once processed and analyzed, will allow scientists to detect changes in cloud structure, cloud top cooling rates, convective cell development or phenomena that may precede a tornado, hurricane or other severe weather events that require advance warnings for the public. The SRSOR capability is expected to be fully operational on the GOES-R satellite scheduled for launch in late 2015.

These efforts serve as a prime example of a successful partnership between NOAA and university researchers. CIMSS scientists have a long history of marshaling new technologies from research to operational mode. Many of those technologies, tested by CIMSS scientists in the research environment, have become critical tools used by the National Weather Service or the National Hurricane Center. SSEC, in turn, has the capability and expertise to capture satellite data via its rooftop array of dishes, archive and serve the data over the long term through its data center, enabling access by scientists around the world for research purposes.

SSEC will make SRSOR data available as well. According to Schmit, “collecting and disseminating these unique data on such short order shows the power of the government teaming with academia” to produce our nation’s next generation of weather forecasting tools.

By Jean Phillips