When the rains stop

Droughts exact a significant toll on agriculture and the people who make it their livelihood. Crops can be damaged or even wiped out, the lack of rain can transform land into such poor condition that it cannot be used for planting or grazing livestock, and workers can lose their jobs – costing billions of dollars over the course of a year. Managing a farm or ranch through droughts requires additional planning and even a little luck in the form of unexpected but welcome rain.

Unfortunately, rapidly developing droughts take away time and opportunities for farmers and ranchers to make adjustments. So scientists have been working on developing tools and methods to provide them with information about conditions and trends to help mitigate the impact. The new twist is that scientists are going out into the field to discuss this work with farmers and ranchers, who then share their personal experiences with drought, including how and when they need to make decisions. The end result is that farmers and ranchers gain a better understanding of what is possible with the available data and scientists learn what information is vital to them.

For Jason Otkin, a researcher with the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS), the effort began in early 2012 with a collaboration led by Martha Anderson of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to investigate improved detection of rapidly developing droughts, known as flash droughts.

Through the use of satellite data, CIMSS scientist Jason Otkin works with farmers and ranchers to help them better prepare for future flash droughts. Credit: SSEC

“Flash drought are droughts that develop very rapidly over the course of a few weeks to a few months,” explains Otkin.

The timing of the collaboration would prove to be auspicious.

“That happened to be the same year that we had the 2012 drought across the central U.S., which was a classic flash drought,” says Otkin.

Otkin and his colleagues are using satellite data to study flash drought conditions. Anderson and Chris Hain, a scientist from NASA, developed the Evaporative Stress Index (ESI) which uses satellite thermal infrared imagery from satellites such as GOES, MODIS, VIIRS, and SEVIRI to compare the “amount of moisture given off by vegetation and the land surface” – known as evapotranspiration – to the potential for evapotranspiration, using such factors as temperature, wind and dewpoint. Then they can compare that information with what they would expect for a particular area based on its climatology.

Using the ESI, Otkin has been investigating not only how to best detect flash droughts, but also to understand when and where they tend to occur most frequently.

More recently, Otkin has begun spending time away from the office meeting with ranchers and farmers in North and South Dakota as part of a collaboration with colleagues at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the National Drought Mitigation Center.

One key component of their interactions is finding out how realistic and accurate the ESI tool is based on what the farmers and ranchers remember regarding actual conditions. In one case, ranchers in Rapid City, SD were able to help verify ESI maps that showed significant differences in conditions just miles apart – the luck of one small strip of land receiving rainfall that surrounding areas had missed.

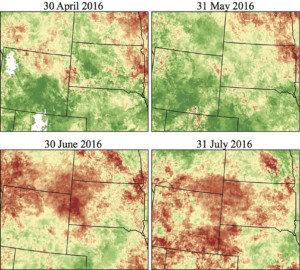

Maps showing the Evaporative Stress Index at monthly intervals from the end of April until the end of July 2016. Red colors denote drier than normal conditions, whereas green colors indicate more favorable conditions. Credit: Jason Otkin

While the verification is anecdotal, “their information is a very important source of ground truth,” notes Otkin.

As another way to test their research results, the researchers gave a survey to farmers and ranchers who experienced a flash drought in western South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska and Montana in 2016. Questions focused on their recollections of when conditions began to decline, from plant health to soil moisture to water levels.

“We tried to use that like a crowd-sourced means of getting qualitative information to then verify these datasets… if you can use them in aggregate, they become very useful. You can start to see patterns, spatial patterns, temporal patterns,” says Otkin.

Just as important has been learning from farmers and ranchers about how and when, and in what formats, information about drought conditions is most useful and relevant to them. As Otkin explained, it is a matter of perspective. Out of necessity, farmers and ranchers start making decisions during the winter, long before any of the drought prediction tools would be available. So the goal becomes looking at what decisions scientists can help inform during the growing season, giving farmers and ranchers the edge they need to survive the drought, let alone thrive.

Improving the resolution of the ESI product would help provide that edge with greater detail. The current resolution of the ESI is 4km, but a special version of it has 30m resolution that provides detailed information over a single field.

Otkin will also meet with specialty crop growers in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Missouri for the first time in early 2019 in a project led by Tonya Haigh from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Noting that specialty crop growers often get overlooked in drought discussions because of their smaller size, Otkin is eager to include them in his work. He’ll share with them the current version of the 30m resolution ESI product to see how it might meet their particular needs.

Through these efforts Otkin and his colleagues have begun developing long-term relationships that they hope will allow them to trade information to improve the drought products and improve outcomes for those who make their living in agriculture. Having grown up on a farm in Minnesota, Otkin remembers the complicated process and nature of managing crops and livestock, and he also understands that gaining the trust of farmers and ranchers takes time. His personal connection, enthusiasm and dedication to the work are clearly evident as he discusses his research and that of his colleagues.

“I’ve always liked the long game… droughts take a long time [compared to a tornado or other weather events]. So as [those conditions] slowly accumulate, one day at a time, it becomes very interesting.”

This work was funded by the NOAA Climate Program Office Sectoral Applications Research Program (SARP).