Hurricane slowdown

Some hurricanes are moving more slowly, spending increased time over land and leading to catastrophic local rainfall and flooding, according to a new study published today in Nature (June 6, 2018).

While hurricanes batter coastal regions with destructive wind speeds, study author James Kossin, says that the speed at which hurricanes track along their paths – their translational speed – can also play a role in the damage and devastation they cause. Their movement influences how much rain falls in a given area.

This is especially true as global temperatures increase.

The South Carolina Coast Guard captures images of the major flooding brought on by Hurricane Harvey during rescue operations August 31, 2017. Harvey’s track nearly stalled over Texas as it continued to drop record-breaking rainfall over Houston and surrounding areas. Credit: U.S. Air National Guard Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez

“Just a 10 percent slowdown in hurricane translational speed can double the increase in rainfall totals caused by 1 degree Celsius of global warming,” says Kossin, a researcher at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Center for Weather and Climate. He is based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The study compared 68 years (1949-2016) of worldwide hurricane track and intensity data, known as best-track data from NOAA to identify changes in translational speeds. It found that, worldwide, hurricane translational speeds have averaged a 10 percent slowdown in that time.

One recent storm highlights the potential consequences of this slowing trend. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey stalled over eastern Texas rather than dissipating over land, as hurricanes tend to do. It drenched Houston and nearby areas with as much as 50 inches of rain over several days, shattering historic records and leaving some areas under several feet of water.

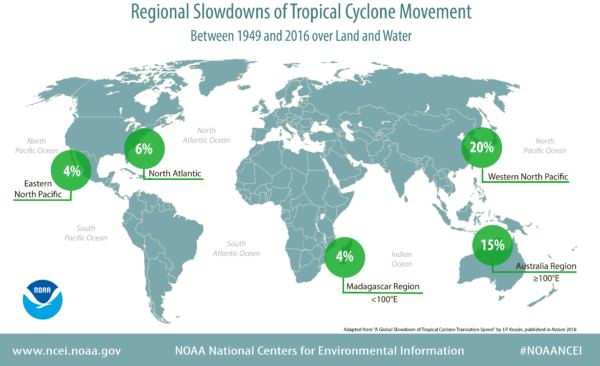

How much hurricanes have slowed depends on where they occur, Kossin found. He says: “There is regional variation in the slowdown rates when looking at the 10 percent global average across the same timeframe.”

The most significant slowdown, 20 percent, occurred in the Western North Pacific Region, an area that includes southeast Asia. Nearby, in the Australian Region, Kossin identified a reduction of 15 percent. In the North Atlantic Region which includes the U.S., Kossin found a six percent slowdown in the speeds at which hurricanes move.

When comparing hurricane tracks during their time over land and water, the study reveals regional variability in the slowdown rates of hurricane translation speeds. Credit: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information.

When further isolating the analysis to hurricane speeds over land, where their impact is greatest, Kossin found that slowdown rates can be even greater. Hurricanes over land in the North Atlantic have slowed by as much as 20 percent, and those in the Western North Pacific as much as 30 percent.

Kossin attributes this, in part, to the effects of climate change, amplified by human activity. Hurricanes move from place to place based on the strength of environmental steering winds that push them along. But as the Earth’s atmosphere warms, these winds may weaken, particularly in places like the tropics where hurricanes frequently occur, leading to slower-moving storms.

Additionally, a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor, potentially increasing the amount of rain a hurricane can deliver to an area.

The study complements others that demonstrate climate change is affecting hurricane behavior.

For instance, in 2014, Kossin showed that hurricanes are reaching their maximum intensities further from the tropics, shifting toward the poles in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. These shifts can deliver hurricanes to areas – including some heavily-populated coastal regions – that have not historically dealt with direct hits from storms and the devastating losses of life and property that can result.

Another study, published in April by researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, used a modeling approach to look at what would happen to hurricanes under future climate projections. Using real hurricane data from 2000-2013, the researchers found future hurricanes will experience a 9 percent slowdown, higher wind speeds, and produce 24 percent more rainfall.

“The rainfalls associated with the ‘stall’ of 2017’s Hurricane Harvey in the Houston, Texas area provided a dramatic example of the relationship between regional rainfall amounts and hurricane translation speeds,” says Kossin. “In addition to other factors affecting hurricanes, like intensification and poleward migration, these slowdowns are likely to make future storms more dangerous and costly.”

The study was supported by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

By Eric Verbeten